Systems, Structure and Self-Expression

Where Alphabets Were Born: A Journey Through Ohrid's Sacred Waters and Ancient Scripts

From the Byzantine basilicas of ancient Lychnidos to the monastery where Cyrillic script flourished—a photographic exploration of Ohrid's role as the cradle of Slavic literacy and spiritual heritage

TURQUOISELIFEBALKANSPLACESTRAVELTRAVELJOURNALISM

8/14/20258 min read

The Lake of Deep Time

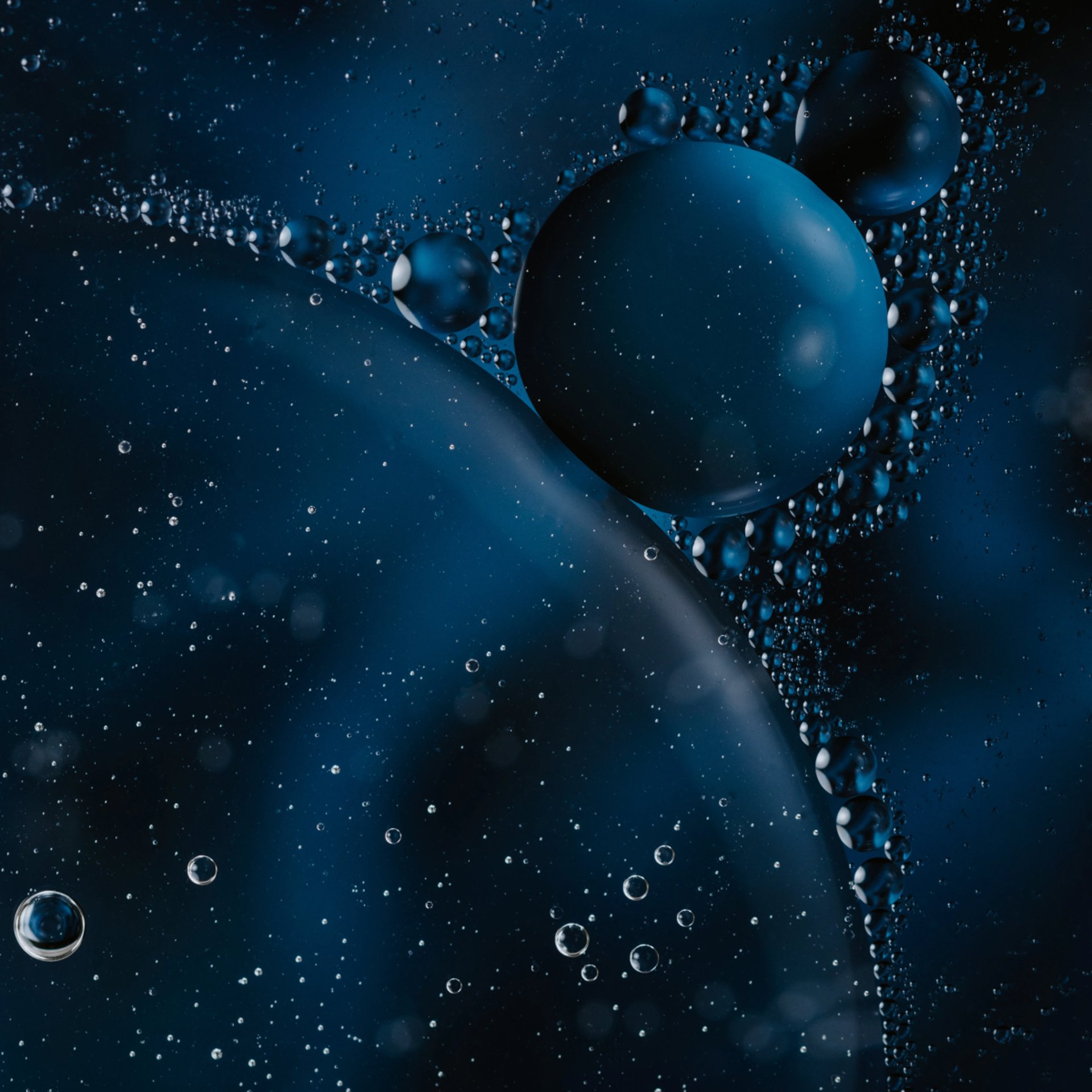

Standing at the edge of Lake Ohrid in the early morning light, I'm confronted by one of Europe's most profound natural phenomena. This ancient body of water, dating from the pre-glacial era, stretches before me like a mirror reflecting three million years of geological history. With an estimated age of around three million years and a maximum depth of 300 metres, lake Ohrid is one of the oldest and deepest natural lakes in Europe.

The clarity of the water is almost supernatural—crystal clear water, which is visible down to 22 meters, of a total maximum depth of 286 meters. This transparency seems fitting for a place that would become synonymous with intellectual and spiritual clarity. As a researcher, I'm drawn to the scientific significance of what lies beneath these pristine waters. Lake Ohrid is home to over 200 endemic species and is a critical habitat for migratory birds. As such, this is considered the most biologically diverse lake on earth.

But beyond its biological importance, Lake Ohrid represents something even more remarkable—a geographical meeting point where East and West, ancient and modern, sacred and secular have converged for millennia. The Lake Ohrid region, a mixed World Heritage property covering c. 94,729 ha, was first inscribed for its nature conservation values in 1979 and for its cultural heritage values a year later.

The morning mist rising from the lake's surface carries with it the weight of history. This is where the foundations of Slavic literacy were laid, where Byzantine art flourished, and where one of Christianity's most important intellectual traditions took root in the Balkans.

Lychnidos: The Light Bearer's Ancient Foundation

The city that would become Ohrid began its recorded history as Lychnidos, a name that translates to "city of light"—prophetic, given what would unfold here centuries later. Archaeological excavations have revealed the profound significance of this ancient settlement. Seven basilicas have thus far been discovered in archaeological excavations in the old part of Ohrid. These basilicas were built during the 4th, 5th and beginning of the 6th centuries and contain architectural and decorative characteristics that indisputably point to a strong ascent and glory of Lychnidos.

Walking through the old town's stone-paved streets, I'm struck by the layers of civilization literally built one upon another. The structure of the city nucleus is also enriched by a large number of archaeological sites, with an emphasis on early Christian basilicas, which are also known for their mosaic floors. These mosaics, fragments of which can still be glimpsed in excavated sites, speak to a level of artistic sophistication that established Ohrid as a cultural center long before its medieval golden age.

The transformation from Lychnidos to Ohrid reflects the broader cultural shifts that swept across the Balkans. While the earliest inhabitants here were the Greek Illyrian tribes, the Southern Slavs arrived during the 6th Century AD and Ohrid eventually became capital of the First Bulgarian Empire, At that point, it started to be referred to as Achrida in written texts, a change from the Greek name Lychnidos.

The Jerusalem of the Balkans

Perhaps no other designation captures Ohrid's spiritual significance better than its traditional title: "Jerusalem of the Balkans". This isn't merely poetic hyperbole. Ohrid is known for once having 365 churches, one for each day of the year, creating a sacred landscape unmatched anywhere in the Orthodox world.

The concentration of religious architecture here tells the story of Ohrid's role as both a spiritual and intellectual powerhouse. Each church, monastery, and chapel represents not just a place of worship, but a center of learning, artistic creation, and cultural preservation. The city became a refuge for scholars, artists, and holy men fleeing various political upheavals throughout the medieval period, creating a unique synthesis of Byzantine, Bulgarian, and local Macedonian traditions.

The town of Ohrid is one of the oldest human settlements in Europe and a testimony of Byzantine art, with more than 2,500 square metres of frescoes and over 800 icons of world significance. These numbers are staggering—they represent one of the largest concentrations of medieval Christian art anywhere in the world, preserved in a setting that has changed remarkably little over the centuries.

Saints Clement and Naum: The Alphabet Makers

The true transformative moment in Ohrid's history came with the arrival of Saints Clement and Naum, disciples of the legendary brothers Cyril and Methodius. These figures represent more than religious history—they are the architects of Slavic literacy itself.

Naum of Ohrid or Naum of Preslav (c. 830 – December 23, 910), was a medieval Bulgarian writer and missionary among the Slavs, considered one of the Seven Apostles of the First Bulgarian Empire. He was among the disciples of Cyril and Methodius and is associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic script.

The intellectual achievement of these men cannot be overstated. Working in Ohrid's monasteries, they didn't merely translate existing texts—they created the very foundation of written Slavic languages. St. Naum of Ohrid (Sveti Naum in Macedonian), was a medieval scholar and writer, who together with Saint Clement continued the task of spreading Christianity among the Slavic speaking people of the region. Building upon the work of the sainted brothers Cyril and Methodius, St. Naum is associated with the creation of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts that would eventually be used by hundreds of millions of people.

The Ohrid Literary School they established became one of medieval Europe's most important centers of learning. Slav culture spread from Ohrid to other parts of Europe, carrying with it not just religious teachings, but entire systems of writing, education, and cultural expression.

The Monastery of Saint Naum: Where Letters Were Born

Twenty-nine kilometers south of Ohrid city, positioned dramatically on a cliff overlooking the lake, stands one of the most significant monasteries in the Orthodox world. The monastery was established in 905 by St Naum of Ohrid himself. St Naum is also buried in the church.

Approaching the monastery on foot, following ancient pilgrimage paths, I'm struck by the power of this location. The original monastery was built on this very same plateau, in 905 by Saint Naum of Ohrid himself. Taken down between the 11th and 13th century, the monastery was then rebuilt in the 16th century as the multidomed byzantine structure that you see today.

The current structure, with its distinctive domes and frescoed interior, houses not just religious artifacts but the very instruments of cultural transformation. Here, in chambers overlooking the pristine lake, scribes worked to perfect the Cyrillic alphabet, copying manuscripts that would preserve Slavic culture through centuries of political upheaval.

Saints Clement (840-916) and Naum (835-910) were native Macedonians. Both had been disciples of the brothers Kiril and Metodi, the inventors of the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts. Clement founded the Monastery of St Clement in Ohrid, and invited his former fellow disciple Naum to help him teach the scriptures.

The monastery's educational mission continued for centuries. Since the 16th century, a Greek school had functioned in the monastery, maintaining its role as a center of learning long after the medieval period.

Contemplation on Sacred Waters

The waters surrounding the monastery possess an almost mystical quality that seems designed for contemplation. Each morning during my stay, I find myself drawn to the rocky shores where natural springs emerge from underground sources, creating a constant, gentle sound that the monks have described as the lake "breathing."

These springs represent more than natural phenomena—they symbolize the continuous flow of wisdom and tradition from this sacred place. The monastery gardens, maintained by the monastic community, contain herbs and plants that have been cultivated here for over a millennium, creating a living connection to the agricultural wisdom of medieval times.

The therapeutic qualities of this environment extend beyond the spiritual. The negative ions generated by the springs, combined with the lake's pure air and the rhythm of monastic life, create conditions that modern research recognizes as beneficial for mental clarity and stress reduction. Sitting in silent meditation at dawn, watching the lake surface mirror the sky, I understand why this place became a center of intellectual and spiritual achievement.

The Living Script: Cyrillic in Contemporary Macedonia

The legacy of Saints Clement and Naum extends far beyond museum displays and historical texts. Cyrillic script remains the living writing system for millions of people across the Balkans and Eastern Europe. In North Macedonia, the connection to this heritage is particularly strong and visible.

Walking through contemporary Ohrid, I observe how modern Macedonian Cyrillic signage creates a direct visual link to the medieval scripts developed in these very streets. The letterforms may have evolved, but the fundamental system created by the Ohrid school continues to serve as the foundation for written communication.

Local cultural institutions maintain active connections to this heritage through calligraphy workshops, manuscript preservation projects, and educational programs that teach both the history and practice of traditional scriptorial arts. The national celebration of Saints Cyril and Methodius Day each May 24th transforms Ohrid into a focal point for pan-Slavic cultural identity, with delegations arriving from across the Orthodox world.

Cultural Resilience and Continuity

What strikes me most profoundly about Ohrid is how it embodies cultural resilience without resorting to mere preservation. This is not a place frozen in time, but rather a community that has managed to maintain its essential character while adapting to contemporary realities.

The city's designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site reflects international recognition of this achievement. North Macedonia's side of Lake Ohrid was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979, with the site being extended to also include the cultural and historic area of Ohrid in 1980. This protection helps ensure that future generations will be able to experience the same combination of natural beauty and cultural significance that has made Ohrid remarkable for over fifteen centuries.

The modern challenges facing Ohrid—tourism pressure, development tensions, environmental concerns—mirror those confronting heritage sites worldwide. Yet the community's response demonstrates the same adaptability that allowed medieval Ohrid to become a bridge between Byzantine and Slavic cultures.

Reflections on Light and Learning

As my time in Ohrid draws to a close, I'm struck by how the ancient name Lychnidos—"city of light"—continues to resonate. This light isn't merely metaphorical. It's the literal illumination that allowed scribes to work, the intellectual illumination that created alphabets, and the spiritual illumination that drew pilgrims and scholars from across Europe.

The manuscripts created here didn't just preserve existing knowledge—they created new possibilities for human expression and understanding. In an age when literacy was rare and books were precious, Ohrid became a factory of enlightenment, producing not just texts but the very tools that made widespread literacy possible.

The photographs I've captured during this journey—Byzantine frescoes catching afternoon light, the lake's surface at dawn, ancient stones worn smooth by centuries of pilgrimage—document more than beautiful scenes. They record evidence of one of humanity's most successful experiments in cultural transmission, a place where wisdom was not just preserved but actively transformed and shared.

Standing one final time at the monastery of Saint Naum, watching the eternal springs flow into waters that have witnessed the rise and fall of empires, I'm reminded that some human achievements transcend their historical moment. The Cyrillic alphabet, born in these monasteries beside this ancient lake, continues to serve as a bridge between thought and expression for millions of people.

In Ohrid's story, I find evidence of humanity's capacity not just to preserve culture but to create tools that expand human possibility. Perhaps that's the most profound lesson from these waters and stones—that authentic cultural achievement doesn't just reflect its time but creates resources for futures we can barely imagine.

Bibliography

Historical and Archaeological Sources:

Curta, Florin. The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500-700. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Kaimakamova, Miliana, et al. History of Bulgaria. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2015.

Snively, Carolyn S. Medieval Art and Architecture at Ohrid. British Archaeological Association, 1995.

Religious and Liturgical Studies:

Dvornik, Francis. Byzantine Missions Among the Slavs: SS. Constantine-Cyril and Methodius. Rutgers University Press, 1970.

Obolensky, Dimitri. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. Praeger, 1971.

Tachiaos, Anthony-Emil N. Cyril and Methodius of Thessalonica: The Acculturation of the Slavs. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2001.

Linguistic and Cultural Studies:

Lunt, Horace G. Old Church Slavonic Grammar. 7th edition. De Gruyter Mouton, 2001.

Schenker, Alexander M. The Dawn of Slavic: An Introduction to Slavic Philology. Yale University Press, 1995.

Vlasto, A.P. The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

UNESCO and Heritage Studies:

Bandarin, Francesco, and Ron van Oers. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Ohrid Region Management Plan. 2020.

Environmental and Limnological Research:

Albrecht, Christian, et al. "Paleoclimate and the formation of sapropel S1: inferences from Late Quaternary lacustrine and marine sequences in the central Mediterranean region." Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 158.3-4 (2000): 215-240.

Föller, Kirstin, et al. "Evolutionary and taxonomic implications of a molecular phylogeny of the endemic gastropod fauna of Lake Ohrid." Hydrobiologia 615.1 (2008): 207-233.

Reed, Jane M., et al. "The last glacial–interglacial cycle in Lake Ohrid (Macedonia/Albania): testing diatom response to climate." Biogeosciences 7.10 (2010): 3083-3094.

Systemic Studio & Publishing © 2026 All rights reserved.